THE SUTON HOO LYRE

....

....

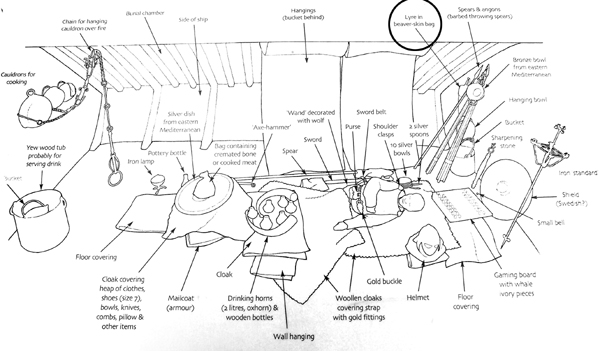

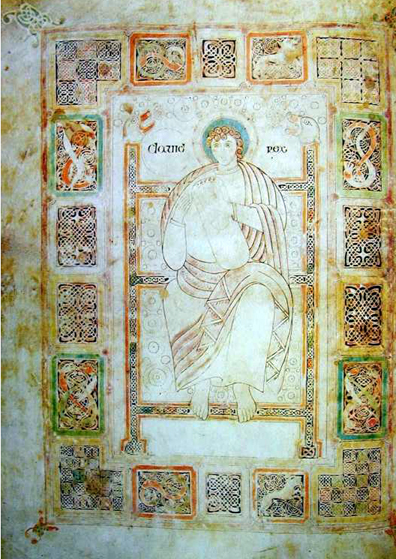

This page documents my copy of the Dolmetsch Workshop reconstruction of the 7th c. lyre found at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk. The first reconstruction of the instrument in 1948 took the form of a quadrangular harp. However the discovery of additional fragments led some years later to another reconstruction in the form of a round germanic lyre. Above left, detail of King David from the Vespasian Psalter, 8th c. Right, the 7th c. ship burial at Sutton Hoo, 1939 excavation.

A diagram of the burial, lyre location circled to the right. "Lyre in beaver skin bag".

The display at the British Museum showing the fragments and the Dolmetsch recreation.

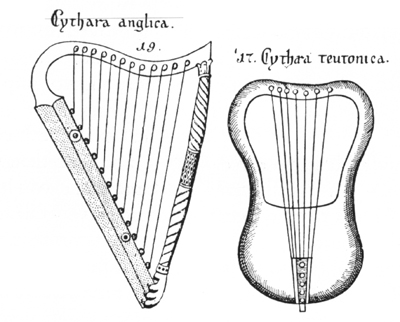

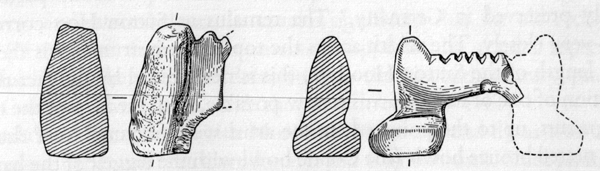

'Cithara anglica' and 'Cithara teutonica' from Gerbert's 'De Cantu et Musica Sacta', reproducing a lost 12th c. MS.

The surviving fragments of the Sutton Hoo lyre assembled

The Dolmetsch Workshop reconstruction.

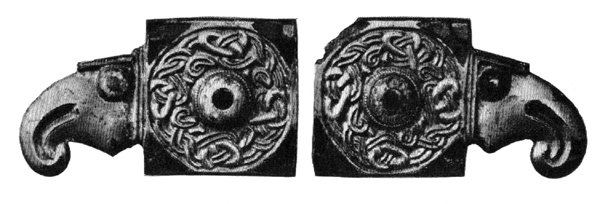

The Dolmetsch Workshop reconstruction, detail of the escutcheons.

Two amber bridges found at Elisenhof, Schleswig in 1967

The Sutton Hoo escutcheons.

My instrument, at my client's request, will be made of the wood I salvaged from the DeGive House in Atlanta (see here) Being pine, and the pieces being lumber of an insufficient width leads me to approach this as a 'constructed' instrument, meaning that the body will not be carved from a single slab of wood as the original (made of field maple, acer campestre) but built up with back, rib and top as separate pieces of wood as later instruments were constructed. This construction will actually increase the structural integrity of the instrument because hollowing the pine to a thinness to permit good tone would ensure splits in the weak parallel grain. The chief effect on the sound of the instrument is the choice of pine in the first place and the fact that it is 'built up' instead of hollowed out is negligible.

++++++

Build Log, 4 July 2013.

The following images show the processing of the reclaimed wood.

.jpg)

Pulling out 100-year old plaster lath nails. This is one of the many studs which I salvaged from the renovation of the 1911 DeGive House in Atlanta's Ansley Park back in 2008. The piece in the background shows three conduit holes. These would have been drilled long after the house was originally built. The knob and tube wiring of the original build was probably updated in the early 1960's when the house was renovated by Frania Tye Lee (Hunt). I have copies of the building permits for "Interior alterations and general repair."

.jpg)

This cutoff is the remainder after my last dulcimer from this wood. It will be the solid yoke of the lyre since it is free of any major damage. The portion to the left shows a split face where the remodelers axed this 4x6 post out of place during the demolition.

.jpg)

Starting to take the quartersawn cuts for the ribs of the instrument. This wood in incredibly dense and resinous. This shot shows how straight and tight the grain is. Truly 'old growth' heart pine.

.jpg)

These consecutive cuts of the tightest grain will be the back and top plate lay-up, after the center grain is trimmed.

.jpg)

Two pieces planed to thickness with the detritus that came out of the board. Two of the modern nails were cut in two by the saws-all or whatever they used to pull these pieces out of the house, which made them incredibly hard to get out. The board to the right illustrates the phrase "they don't make 'em like they used to." On one hand, it shows the days before nominal lumber when a 2x4 was actually a full 2" by 4". However it also shows that the edge of this stud is far from square with the sides.

The form.

The rib is bent and attached to the blocks and the linings are being attached. A blank has been cut for the yoke. Ribs and pegbox are made for a dulcimer of the same material.

The back is attached to the rib. I made a compromise on the design in selecting pieces with conduit holes for the back. On one hand, part of the charm of using this reclaimed wood for the instrument is the various construciton holes, but the original instrument did not have sound holes. So I've decided to restrict the holes to the back of the instrument and leave the front clean, preserving the 'audience side' as the original.

This is something the cittern-maker in me had to do: the addition of a lateral brace just in front of the bridge position. I have not read any report of internal bracing in the few surviving instruments. I believe the thick tops of these instruments and the relatively low string tension and low string-to-bridge angle prevented - or abated - table collapse. But this being my first instrument, and the thought that this is a 'constructed' instrument and outside of the norm anyway - leads me to ere on the side of caution when making assumptions about the structure. I have even arched the table brace slightly to put some upward tension on the table. The brace of the back bisects one of the conduit holes, a trick I did with the first DeGive dulcimer to show through the internal structure. Note that the linings almost converge on the rib. Seeing as my rib thickness is only about 2.5mm and the original instruments which were carved out of a single block of wood probably had sides of as much as 5mm the extra bulk can only help with the rigidity.

I came across another depiction of king David and his lyre from the 8th c. Durham Cassiodorus. This is a 5-string instrument and he appears to be playing the strings open from the front, as opposed to the posture in the Vespasian Psalter.

The yoke is attached with a slotted joint. The cut of the wood is not very attractive so I think I'm going to laminate some quartersawn facing in the opposite direction in the same plane as the soundboard grain.

The yoke is trimmed. A block of wood awaits being turned into a bridge.

Facing to cover the yoke grain.

The tailpiece is made and the bridge is roughed out

.jpg)

I guess this is how you tap the end pin hole for a lyre.

.jpg)

The original instruments were made presumably without a drop of glue and relied on a pinned mortise to hold the yoke on and nails to hold the top to the carved body. My construced version does not need the nails. But I'm adding them for two reasons: to complete the traditional look and because I have all these nails I pulled out of the DeGive wood. Waste not!

.jpg)

The nails are pounded straight and I'm starting to cut them to length and regrind a tip. A tedious process made more fun by listening to 'Rocky Top' by the Osbornes on repeat. Their recording is 2:38 long and it took me about an hour and a half. So I should have it about memorized by now!

.jpg)

A test peg fitting. The nails are in and the finish is on. I did a simple mineral oil with wax top coat.

++++++

September 5, 2013

The instrument is complete.

++++++

Lyre chap book:

From Rupert Bruce-Mitford's 'Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archeology. . .'

"C.L. Wrenn called the discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial 'perhaps the most important happening in Beowulf studies since the Icelander Jon Grimur Thorkelin made his transcripts of the Beowulf MS. and from them published the first edition of the poem.'"

"The new reconstruction was made, from detailed drawings supplied by the British Museum, in the Arnold Dolmetsch workshop at Haslemere, under the direction of Mr G.H. Carley. The cost was met from a grant made by the National Geographic Society of America."

"The validity of the reconstruction is supported by comparison both with fragments of lyres of slightly later date found in Germany and with contemporary manuscript illustrations. The hollow arms are similar to those of lyres from Oberflacht and Cologne, and the bridge on our replica is a copy of the earliest known bridge, from Bora i Halle, Gotland."

"There is no record of the tuning of Saxon instruments, so the reconstruction has been tuned to a pentatonic scale, characteristic of early folk music."

"Despite the shallowness of the resonator and the absence of sound holes, the tone is vibrant and surprisingly robust. Professor Donald K. Fry of the State University of New York has informed me that during a recent experimental hearing a copy of our replica was easily audible at the back of a large hall with rather poor acoustics."

"Beaver hairs surviving as dark patches on the outside of the frame of the Sutton Hoo instrument show that it was kept, and burried, in a beaver-skin bag, with the fur inwards"

From Frederick Crane's 'Extant Medieval Musical Instruments: A Provisional Catalogue by Types':

"Seven Germanic lyres and seven bridges are known. The two instruments from Oberflacht have been mentioned in print quite often, as well as the one form Sutton Hoo in its earlier reconstruction as a harp, but the other objects are a little less well known."

"The preserved fragments consist of the yoke, with six pegholes, the upper part of the arms, some fragments of the body, and two gilt bronze plaques representing bord's heads. The yoke was joined to the arms by a tenon-and-mortise joint at each end; rivets to hold the joints are attached to the backs of the metal plaques."

"It is a sad minor example of the waste of war that of the actual lyres that were partially preserved, two of the three in Germany were destroyed some time between 1939 and 1946. The St Severin's Church lyre and its records were bombed in Cologne. In Berlin, where the complete lyre from Oberflacht (it had no sound holes) was preserved in a tank of alcohol, Russian soldiers drank the alcohol, so liquidating the bits of wood. The sixth-century bronze bowl from Gilton in Kent with its silver patch depicting a lyre player was destroyed by bombing in Liverpool. Only one of the German lyres survives, at Stuttgart, incomplete and in fragments. So the Sutton Hoo and Taplow remains are of outstanding importance."

-Rupert Bruce-Mitford

The reconstructed Sutton Hoo lyre . . .both on exhibit at the British Museum and also in the minds of Anglo-Saxonists, is an instrument that is attractive to the eye and pleasing to the ear. And in the hands of performers like Benjamin Bagby of the early music group Sequentia, who has recorded portions of Beowuf with it and recently gone on tour with his impressions of how that poem might have sounded, it is an instrument of expressive power.

- Robert Boenig from the journal Speculum, 1996