Lutherie chap book:

INSTRUMENTS

PLEASE NOTE. . .I AM NOT TAKING COMMISSIONS AT THIS TIME AND HAVE NO INSTRUMENTS CURRENTLY FOR SALE. . .I DO NOT FABRICATE PARTS FOR INSTRUMENTS. . .MY DRAWINGS ARE NOT CURRENTLY FOR SALE

The following is a descriptive list of my past instrument projects. I am currently focused on Appalachian instruments, specifically the open back 5-string banjo.

Due to my approach of tailoring each instrument to the player's needs, as well as for the changeable nature of material costs, I have not posted prices on this website.

'Deco'

12-string guitar

Just starting. Se here for my drawing.

Vihuela

Project

Still in progress. See here for build log.

Sutton

Hoo Lyre

My version of the Dolmetsch Workshop reconstruction. See here.

The

DeGive Dulcimer

My name for an instrument made out of salvaged wood from the DeGive House

in Atlanta.

I aquired enough wood to make many instruemnts. But the piece with the

most interesting defects and straightest grain was made for this first

instrument. Complete details of the project are

here .

The instrument won "Jury's Pick" in Connexion Gallery's 'Less is More' 2010: Simplicity Leads to Sustainability. Click here for the prospectus.

Slit

Drums

A set of rectangular wood 2-tone drums based on Stockhausen's specifications

for the instruments required for "Zyklus" and "Kontakte".

Complete

details of the project are

here .

Stockhausen's

Heaven's Door

I received the commission from Stockhausen's percussionist, who lives

here in Atlanta, to build the second iteration of an instrument he literally

dreamed up for a composition of the same name. It was a mammoth undertaking,

if nothing for the shear size of the instrument, but most notable for

the fact that I am not a percussion instrument maker! There was much trial

and error as we intentionally did not wish to reverse engineer the first

iteration. After the instrument's debut I was delighted to be able to

write an account of the making of the instrument for publication in the

Galpin Society Journal. Following is my abstract:

"In June 2006 the world was introduced to a new musical instrument conceived by the ground-breaking German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen for the performance of his piece entitled Heaven's Door, the forth composition in a series titled KLANG/ - Die 24 Stunde des Tages. The present article concerns the documentation of the instrument created for that performance as well as a second iteration of the instrument, which was constructed by the author. This second instrument was modified aesthetically and in its acoustical mechanics under the guidance of Stockhausen's percussionist, Dr. Stuart Gerber, in perpetration for the North American debut of the piece in Charleston, South Carolina at the Spoleto USA festival in June, 2007. The article explores the challenges of creating the vertically oriented struck plate idiophone (conceived of by the composer in a dream) and the relationships between composer, performer and instrument-maker in the development of a completely new instrument."

Complete details of the project are here .

The

Hammack Dulcimer

A copy of Smithsonian accession #65.0175, from my own drawing. The instrument

is believed to have been owned by the Confederate cavalryman Charles Hammack,

dated between 1848-1885. In walnut with painted black purfling and beveled,

overlapping edges as the original. My version deviates only in practical

details for the modern player: modern fretwire and fret placement and

individual string holders (brad tacks) at the end rather than the single

one of the original. The original had a real butterfly pressed into the

varnish of the lower back, which I will reproduce on request. UPDATE 06/16/05

- I have completed a version as the original with staple frets lying only

under the first two courses. Project log for the construction of this

instrument here.

The

Boucher Banjo

An instrument based on Esperance Boucher’s pre-Civil War instruments,

characterized by a “serpentine” headstock. True to the

originals, my version has a laminated rim, friction pegs and s-shaped

occipital 5th string detailing. These instruments were originally

fretless, but many aquired frets over the years and I myself have added

frets to mine. Maple neck, mahogany rim, bound rosewood fretboard,

ebony pegs.

Parlor

Banjo

Following the success of my Boucher model I made a smaller, more delicately

proportioned instrument based on several examples I have seen locally

which date from just after the Civil War. It has the common clover-leaf

peghead, v-shaped neck profile and finely turned dowel stick with a through-body

construction. The tailpiece is held on with gut in the traditional

way. My first version of this instrument was made with a body made

up of 6 joined pieces turned on the lathe, (a method described in the

"Foxfire 3" book by maker Dave Pickett) with a 10" hand-stretched

goatskin head. The present model has a 12-ply laminated rim.

A new parlor banjo is complete! This one with a figured maple neck and figured sapele body with boxwood fittings. View details

Tenor

cittern after DaSalo

A scaled-up version of the more common 530mm Ashmolean model. See my Cittern

page for build logs

Cittern

after DaSalo

My most widely researched and oft produced instrument. I fell in

love with the sight of it in the Early Music Shop (Bradford, UK) catalogue

in the mid 80’s I obtained one of their kits (which deviates

considerably from the instrument on which it was based: the Ashmolean

model) which I still uses as my primary performance instrument although

I have made several others from scratch. One of which is in use by

an early music group in Ann Arbor. My instruments vary in detailing

but most commonly include a striped, wedge-shaped back, finely turned

scrolls and a geometric finial rather than a carved head. Body and

neck of maple or sycamore, gothic rosette, scalloped fingerboard to improve

intonation, pine or sitka spruce top. UPDATE 09/01/05 - I touched the

original! I had the chance on our Scotland/London trip to swing by the

Ashmolean in Oxford and actually have a couple of hours of inspection

time of the Da Salo. Amazing! Unfortunately time constraints and the bizarre

restrictions regarding photography in the map and print room (where study

of the instrument collection is conducted) prevented me from doing the

documentation I would like. But the one-on-one time with one of my favorite

instruments was invaluable. My future citterns will benefit. See dedicated

page

Viola

d'amore after Amand

A 12-string (6/6 arrangement), scalloped body instrument, my version lies

between the one in the Smithsonian collection which has vaulted back and

top, and an earlier instrument in a collection in Vienna. The result

is an instrument with a curved top and flat-and-angled back reminiscent

of the earliest viols but producing a sound faithful to the more typical

arched-top-and-back instruments. This was an experiment made early

in my career and I look forward to returning to a more faithful reproduction

of the Smithsonian instrument. The viola d'amore will certainly become

a life-long passion of documentation for me. Between museum and private

collections I have already documented 6+ instruments.

Lira

da Braccio

Leonardo da Vinci's favorite instrument. Mine is a 5/2 string arrangement

based on pictorial evidence. Boat-shaped with an arched (not vaulted)

top and striped back, typical of the earliest 15thc representations.

Below are my latest forms, one for a later-date Lira da braccio and a similarly shaped Lyra viol.

Baroque

Guitar after Choc. 1602

An instrument I made from a documentation of the original in the book

"Geometry and Perportion and the Art of Lutherie", a splendid book which

gives in scientific method a study of 20+ excellent specimens of early

instruments. The book was not intended for use as a practicum, but the

drawings provided were enough for me to produce a reasonable facsimile.

I am in the process of my second copy. By chance I came across a copy

made by an English maker while at the 1999 Lute Society gathering at Case

Western and I noted with bemused interest that his instrument was, in

every dimension, a good 10% smaller than my own. One of us is misinformed.

This version showing a non-historic rosette. The original has an inset wood rosette similar to a cittern's instead of the more traditional 'wedding cake' tiered parchment rosette of later baroque instruments. This particular model is my 'ren fest' instrument with a simplified design to lower cost and better survive abuse. I have started a dedicated page to the construction of my third iteration of this instrument here.

Honduran mahogany neck for a flamenco rough cut. And my newly completed (2015) Torres form waxed

Kiddie

Baroque

Too

silly for a synopsis. Go here and be amused.

Symphonia

A type of early hurdy-gurdy, prevalant in England and the continent by

the 13thc. My starting point was a drawing by David Kronberg, which I

have modified. See here for my build log.

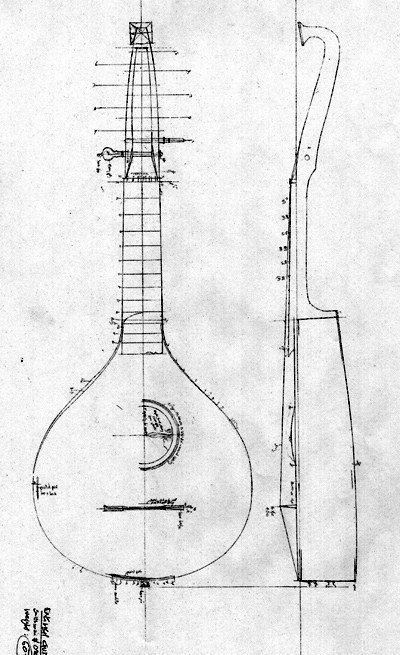

Flat-back

Mandolin

I have made several 'Irish' instruments. The most notable having

c-shape soundholes as found on early fiddles and a striped back of mahogany

and cherry, reminiscent of citterns and baroque guitars.

Scheitholt

Several varieties based on my research of instruments in the Smithsonian

and Met collections. I have made faithful reproductions as well as

my own interpretations.

Vielle

after Memling

Perhaps the most common model being produced, from the famous painting

by Hans Memling. My starting point is the drawing for the EMS kit,

however I have made tracings of other maker’s interpretations over

the years and combined with my own careful study of the source painting

have arrived at my own model.

Vielle

by Betsill

After years of research on early fiddles I have schemed to make my own

design, taking the most aesthetically pleasing detailing found in the

gamut of pictorial representation and the most advanced of construction

in the spirit of the day. Features a deeply-waisted body with ebony binding,

striped back of ebony and maple, flat spruce soundboard with base bar

and soundpost, 5-string arrangement. Click

here to for more details

Rebec

I have made several 'spade' shaped 3-string instruments having a built-up

body. The present project is the turning of the neck/body shape on the

lathe, thus producing a stock from which can be sawn two instruments.

The body cavity will be hollowed out, a soundboard attached and a bent-back

pegbox added. The instrument will resemble instruments depicted in 'Andalusian'

sources.

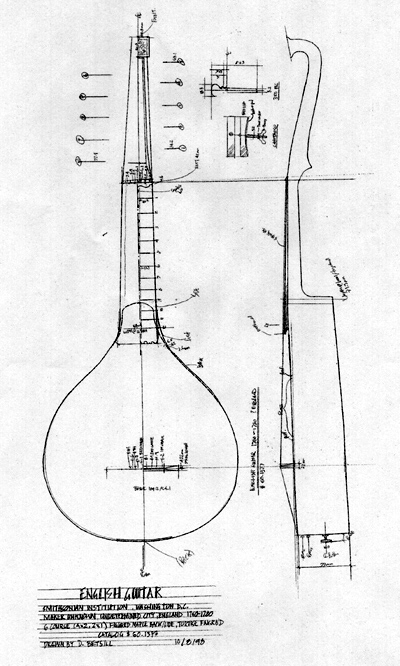

English

Guitar

The name is misleading. Not a guitar at all but a latter-day cittern. I

have undertaken much research of the Smithsonian instruments, featuring

several fine examples by the master himself, James Preston. My instruments

have ranged from small 620mm to “arch English guitar” of my

own design with diapasons similar to a theorbo.

Two instruments form the Smithsonian collection, dating from the late 18th c.

The second instrument drawn above. My study photos fromt he collection.

The

Harton Lute

This is a project not yet undertaken but mentioned for the research I

have done on the instrument by Michele Harton in the Folger Library collection. The

instrument was obtained from the collection of Arnold Dolmetch, who may

have shortened the neck. The only serious documentation of the instrument

prior to my visit was started by Robert Lundburg, but never completed. I

have photo documentation, a soundboard tracing and the longitudinal profile,

but I must return for the lateral sections describing the bowl.

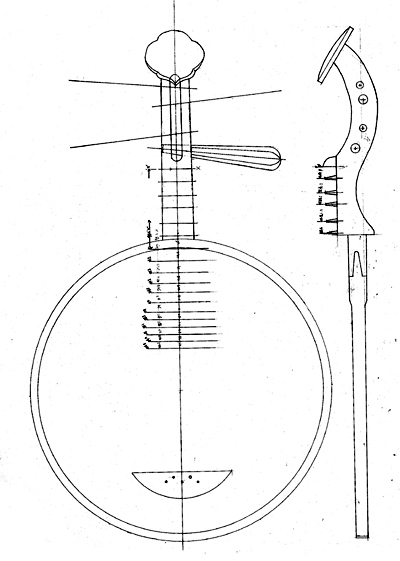

Chikuzen

Biwa

This is a 'practice' instrument I made in preparation for a commission.

The very first musical instrument I attempted was a Japanese samisen (a

banjo-like instrument) for a 7th grade art class performance. I saw a

picture in a book and thought it was the coolest thing I'd ever seen and

was compelled to make one. I was able to unearth nothing further than

the one frontal picture for my creation and wound up using one of my father's

car chamois for the head. It was a crude instrument, but there began my

study and a fascination with Japanese culture that has endured these twenty

years. So I was in a good position to accept this recent commission, having

already documented a fine example here in Atlanta in the collection of

Steven Everett, who's Gamelan group I'm in at Emory University. It's a

4-string Chikuzen. My practice instrument is made out of mahogany which

is easier to work with and more readily available than the mulberry of

tradition. The top, however, is Paulowina, the traditional wood, and I

have located a source in California for the mulberry. The present commission

is to copy an Edo-period instrument in the ownership of a professional

in Colorado. If that instrument is a success it will be sent to Japan

for appraisal by players there to the end that I may produce similar instruments

to be used by students in Japan that are finding them scarce and highly

priced. The biwa-maker is apparently in low quantities in Japan these

days.

View process photos. Check out the Drawing.

A Chinese Yuet Chin I documented about the same time as the Biwa.

Venere

6-Course Soprano Lute

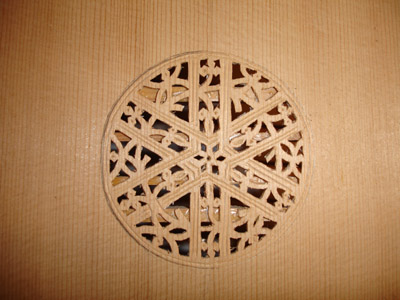

Based on Robert Lundberg's documnetation. Below are a few progress photos.

Progress on the Venere lute belly. The rosette is being cut. The design is glued to the underside for piercing out the negative areas. The paper remains after cutting to help strengthen the rosette and will not be seen from the outside.

Venere rosette. Near completion.

Venere model soprano lute. Maple staves with ebony fillets. I started this about 3 years ago and shelved it with only half the bowl complete. I have now completed the bowl up to putting the linen strips on the stave seams (inside) and completed the striped neck and pegbox. I got it out of mothballs to work on in tandem with the biwa project. Lutes from two different sides of the planet. An ammusing exercise.

Organ

Restoration.

A new aquisition for restoration. This is a suction-type bellows-action

"missionary's organ" possibly dating from the Civil War. The

ivory keyboard is in excellent shape, except for some bad springs causing

the uneven appearance. The bellows are completely rotted and the lyre-type

base is in pieces, I'll be working on this for some time.

See an organ restoration that has actually happened rather than just talked about here.

Baroque

Bow

A new baroque bow in cherry with rosewood frog and boxwood finial. I originally

made this bow as an early baroque "clip-in" style, but quickly

realized why they steered away from this cumbersome method. Wanting to

salvage the project, I put a piece of rosewood in the clip notch and made

the finial opperable with a modern screw attachement. This bow has a high

arch and is suitable for my vielles.

Spike

Fiddle.

The

following is a journal entry from a weekend project to make an instrument

loosly based on my Javanese rabab research, just as a wall-hanger. I have

two drawings of excellent instruments in the collection of Steven Everett,

the director of the Emory gamelan group, but have not made the time to

make faithful reproductions.

What, you may wonder, is this. This is a south-east asian 2-string Rabab spike fiddle in the making. First step: carve out the coconut and make fruit salad.

The spike fiddle in progress. The coconut shell is attached to the turned spindle and the goatskin head is attached. To the side is a peg in the making. My model for this instrument is the Indonesian rabab I documented years ago in the collection of Steven Everett at Emory University. but the coconut I had was too small for that instrument so I am making a more generic instrument which is smaller and shows more middle-eastern influence.

Looks good hanging between my straw plantation hat and pircure of Alfred Percival Maudslay at Chichen Itza.

The instrument that was the inspiration for the above project, In a private collection in Atlanta which I documented. It was played by the (then) leader of the Emory Gamelan Ensamble with which I played.

Strumstick.

I

have made one of these instruments and endevored to give it a few details

bebond the factory, like a more elegant teardrop bodyshape which tapers

slightly in rib height from the neck to the end, and a fixed bridge.

Showing the artfully arranged knot hole on the back in figured walnut.

++++++

Instrument resurrection. . .

Monday, January 27, 2014

The Kay Kraft is "restored". I'll call this a refurbishment since the aim was not to take it back to factory but celebrate the years of use and make it playable again. I'm still going to replace the missing bits of purfling on the soundhole and horn. Hanging with my Kay Kraft mandolin.

My pickguard is mahogany but ebonized and then rubbed out a bit. Hides the worst of the damage easily.

The frets were so badly indented on the second string 1st and 3rd position that the recrowning didn't help. But this shot shows an experiment filling in the indentation with superglue. Worked pretty good. Sure beats pulling the frets. Looks so natural, only my luthier knows!

New year's resolution: fix this Kay Kraft. I have had this instrument for 20 years. I saw a big ol' picutre of Patterson Hood from Drive-By-Truckers in this month's Garden and Gun sporting a Kay Kraft just like mine. . except his clearly is playable. Looks pretty cool! Wish I had one! Wait, I do have one. I got this for probably about $75 from Lark in the Morning when I was in college just on sight of the tiny black and white picture in their catalog. Never seen a body shape like that before. Had to have it. It was listed in 'fair' condition. What it had was a completely shot fingerboard, a freaking BULLET hole and a hack wood-putty patch job. On top of that the top was worn through TO THE LININGS on about 2 inches of the upper bout. I discovered this only after peeling back about ten layers of dark varnish. Long story short, it went on the wall.

It was missing most of the fretboard binding which I replaced easily enough and am now - 20 years later - trimming. This shot also shows the sorry state of the frets. I think I'm going to leave the finger grooves in the rosewood and just recrown the frets. That wood is so brittle that pulling the frets I might as well replace the entire fingerboard. It's worth trying to keep for the playing history and historic frets.

The body. . .well. . .not attractive. There was a time when I though, my God, how am I going to cut out that damage and patch in a new square? It appears stable though - thanks to all the gloop inside the body - so I think a nice big pick guard is what is needed here. I may even leave the partial stripping look to tell the story. Just need to replace that soundhole binding. Note wing nut and sliding dovetail neck attachment that facilitated easy neck angle adjustment on these instruments.

++++++

A

Modern Dulcimer.

The

following is a journal entry of an instrument I made for my wife. The

wide lower bout and wide fingerboard is designed for a beginning player.

The asymmetrical body shape and details make this a modern departure from

most of my dulcimers which are 19th c. reproductions.

A new dulcimer for Shannon, nearly complete. It's hard to tell from the photo, but the body is asymmetrical. The back is striped with alternating walnut and maple. The instrument is complete save for the varnishing of the back and sides

Detail shot of the "hook" at the peg head. Only the fingerboard and top are varnished at this point. The scrollwork is inspired by renaissance cittern heads which were made to "hang on the walls of barbershops for the amusement of waiting patrons"

Treadle

Lathe

It's

Alive!! After many months of deliberation over which century I was in,

the un-treadle lathe is working. The result is my interpretation of the

'Williamsburg' treadle lathe, documented by Roy Underhill in one of his

books, with a 1/2hp washing machine motor mounted on it. About two years

ago I built the frame and put a modern ball-bearing/1" dia spindle on

it with the hopes of running it with the treadle and, with the treadle

wheel disengaged, running with a motor as well. The result was an unhappy

marriage of two different centuries. After realizing that opperating a

treadle while turning was NOT fun, the motor was added on a permanent

basis and the wheel remains as a vestigual reminder of a bygone age

Metal

Casting.

My

instruments occasionally need metal fittings. I learned lost wax casting

in college and recently put that to good use for another reason. Below

is a journal entry from mine and my wife's wedding rings.

Mine and Shannon's wedding rings in white gold. Mine has a Unicil lettered motto "perfruere cursum" ("Enjoy the journey"). Her's has four bezel-set cabochon rubies. Both based on 11th c. celtic designs. I had help with the casting from my old professor, Rob Jackson, at the University of Georgia metal lab, where I first learned lost wax casting over 10 years ago.

Detail shot.

++++++

LUTHERIE

I have now been making musical instruments for half my lifetime, as I claim to have made my first accomplished instruments at the age of fifteen. I refer to a rather unrefined but entirely playable dulcimer and my first cittern, which came from the Early Music Shop kit. My other activities in the arts - music, painting, architecture - all fall short of the ability of lutherie to give me complete use of my interest. In lutherie is the splendid marriage of art and science. Although I cannot at present consider myself a professional (I have sold only a small quantity) I will never loose sight of that goal.

This may seem a strange way to tell the story of my work as a luthier, but I have always taken as much inspiration from the people I meet as the craft I am learning. One peculiar aspect to my pursuit is the fact that I have never had a person to consider my mentor. Unlike Stradivarius who had his Amati, there is no one person who I can claim as my mentor to initiate, if not assure, success as a professional luthier. But on reflection I have not one source, one viewpoint, but a strange assemblage of puzzle pieces that I have made use of in my own way and give me altogether, perhaps, a complete picture. What follows is a tribute to those who have helped me on my journey. This rambling is as much a personal diary as it is intended for any use by those actually interested in my work. Does such a person exist? Read on.

Jean

Crepeau.

If there was ever a figure that came close to a mentor it was he.

Although Jean considers himself more of a musician than a luthier, I nonetheless

attest to his ability to produce some of the finest instruments I have

seen. A French-Canadian who plays a large variety of stringed instruments,

I first met Jean at the Georgia Renaissance Festival in 1991, the year

I moved to Atlanta to go to school in Athens. In fact, he was one

of the very first acquaintances I met upon moving. He was actually

music director of the Festival at the time. Meeting him was also

my first up-close meeting with a lute. Jean had a steady occupation

with his own furniture restoration business, employing one or two helpers,

also French as I recall. He specialized in finishing and I was

privileged to learn French polishing from him. Over the years I

made visits to his house in East Atlanta for advice on my instruments

and for conversation about early music. It wasn't until 1995-6

that I approached him seriously about being his student. The project

would be the construction of a Venere 8-course lute. It is through

Jean I can claim a sort of royal luthier lineage, for he was a student

of the famous Robert Lundburg. So we followed Lundburg's practicum.

Unfortunately I did not finish the instrument with Jean and after

1999 lost touch with him.

Burge

Searing.

I may have spent the most time with Burge, also an early acquaintance.

Burge for years had a shop, "Handcrafted Dulcimers", in Stone Mountain

village. So he was easily found by me when I first moved to Georgia

- Stone mountain had long been one of my favorite places, from childhood

visits at Christmas. On weekends home from school I would often

divide my time between the Weir's antique shop, "Amaryllis", playing their

"faux Steinway", and distracting Burge from his work. He had a

quaint barn-like structure which still stands at the rear of a courtyard

back from the Main Street of pre-Civil War store-front buildings.

Most of the place was showroom, about the size of a well-apportioned bedroom,

with a narrow workshop space at the rear, visible through plexi-glass

windows. Burge would smoke small black cigars while I rambled on

about what I was trying to do with the latest instrument. He was

always encouraging and never seemed to mind taking time off from his work

to chat. He was also generous with his materials, giving me fret

wire and strings in the days before I knew where to get these things for

myself. Harps and hammered dulcimers made the bulk of his inventory

with a few mountain dulcimers and psalteries, one of which I own and gets

played ritually every year at my church's Christmas midnight mass.

Over time, after my school days in Athens, my visits were less frequent.

The Weir's had closed their shop and indeed, most of the "charming"

shops in the village had ceased to be. I would see Burge at the

Celtic festival at Oglethorpe and every year at the Yellow Daisy Festival

at Stone Mountain. It was a shocker one day about three years ago

when I found he too had closed his doors. However I would get spotty

news of Burge from mutual friends in the Scots circle [at one time Burge

had been a piper in a local band] and I am happy to conclude that by a

chance meeting we have very recently been reacquainted. ADDENDUM November

2010 -- The previous was written in 2004. Sadly I must add this addendum

that Burge passed away in 2008. I have in recent years recieved regular

enquires from folks who have one of his instruments and need a repair,

or are looking to buy one of his instruments and find me on the internet

because of this posting. Please visit the memorial site started by his

son, Eric. http://esearing.com/Burge_Searing

Harry

vas Dias.

Certainly the most opportune acquaintance I have made in the instrument

making world. Who would know that a world-renowned, Dutch baroque

oboe (of all instruments) maker lived in Decatur , GA. I met him

through Martha Bishop who headed the early music group I played in at

the time. I had little knowledge of or inclination towards playing

wind instruments, but through a truly strange course of deductive reasoning

in the pursuit of an instrument that possessed portability (as opposed

to my piano) and durability (as opposed to my various stringed instruments)

as well as volume (as opposed to my dulcimers), virtuosity and a decent

repertoire, I rested on the Baroque oboe. (Being an arcane instrument

was simply an added bonus for me) And, what a stroke of luck, there's

this maker in Atlanta. I purchased one of Harry's instruments [actually

an earlier instrument of his which had returned to him, a copy of the

Stainsby Jr. model in the Edinburgh collection] and was flattered when

he extended his offer for tutelage in performance and reed making, which

I understood was not his custom with uneducated patrons. After

nearly two years of performance study and nagging by me he consented to

make an instrument with me. Although I had no intention of making

oboes for a living, I could not pass up the opportunity to study with

a true master. We began a Denner, but alas, our work was interrupted,

basically, by my 20-something lifestyle. Regret! Perhaps

I will have the opportunity again, but I consider myself quite lucky to

have had the lessons I have had.

Lou

Aull.

I believe I met Lou through Harry. He is of that breed of instrument

maker who approaches the craft through Engineering. This makes

for very logical procedure and a very clean workshop. He

may have made other instruments, but I had heard of his lute making.

But as it was, he had done more playing of the instrument than making.

I learned that he had made a few tours on the college circuit,

even. All this was a surprise considering his day job had something

to do with troubleshooting industrial machines or computer systems or

something of the sort. By the time I met him he was no longer pursuing

instruments. I got the impression that he had "done" lutes and

had moved on to another challenge. Welding, he was doing, at the

time I was hanging around, a period of just less than a year. An

interesting connection, he was a student of George Kelicheck.

He had spent some substantial amount of time with the man and his son

learning the craft. He had learned the method of constructing

the lute bowl ribs using a "wedge" of the body shape, thus making each

rib identical and producing a semi-circular cross section. When

mounted on the wedge, one could put a precise bevel on the rib as that

joint changed angle along the longitude of the bowl. It is a very

"engineer" approach to solving the problem of making a difficult shape,

and the opposite method of an "artistic" maker such as Jean who thicknessed

wood by touch and shaped by eye. And since Jean was my prevailing

master, I found Lou's method to complicated to reproduce. Through

him though I came to appreciate the differences between makers of the

two different "camps" of lutherie. I also got a finishing lesson.

Lou, quite unhistorically, used a spray gun to finish his instruments

with lacquer. I had a compressor but no experience with spray finishing.

He hooked me up with a gun and how to use it and spraying has since

become an indispensable part of my woodworking: more for furniture, thought,

than for instruments.

George

Kelicheck.

A sort of regional early music patriarch, I knew George by reputation

and through stories told by Martha and Lou. I met him only once,

at his compound in Brasstown, N.C., but one day was enough for a lifetime

of reflection. Although trained in Germany as a luthier

in the apprentice-journeyman tradition he had a great interest in embracing

technology and modern materials. He is the man behind the

"Susato" trademark, producing pvc whistles and recorders, and, to be sure,

the world's only plastic crumhorn. I'll never forget the giant

crate of half-finished brown plastic crumhorns I was introduced to on

a tour of his workshops - a great throng of mute, lifeless appendages

awaiting windcaps to breathe life into. There's a funny story

of encountering his whistles in Ireland. I was in central Ireland,

visiting Leap castle, the ancestral home of the O'bannons. The

present owner was Sean Ryan, whom I came to understand holds the auspice

of being one of the finest whistlers in the country. Besides having

the pleasure of tromping around this old castle, closed to the public,

and that was of my own line, I had the great opportunity

to get a music lesson from it's famous owner. I had my nice rosewood

whistle for which I had paid quite allot of money. Sean seemed

unimpressed after playing it a short while. "Well I prefer

these Susato whistles. I believe they come from the States. . .",

he said as he pulled one out of his vest. Imagine my surprise.

I informed him that they were made not two hours drive from where

I lived in Georgia. I had to go to Ireland to find something at

my back door. He preferred them for their crisp, level tone, sharper

than a wooden whistle but still warm, unlike a tin one, and well intonated

across both octaves. Well I bought one as soon as I got home and

have used them ever since. But back to George: I had heard

he was an irascible, unpredictable fellow. Even on

the trip up there, having stopped at a dulcimer maker's shop by chance,

I heard from this maker who had had an offer from Kelicheck for study

but had declined in the end because of his abrasive nature.

I was told I was taking my life into my own hands by taking an instrument

for his evaluation and prepared myself for a trouncing.

I was not disappointed. Admittedly, the instrument I chose to show

was historically confused - an "arch cittern" I called it, though it resembled

some Victorian concoction closer to an English guitar with a bass extension.

It had geared tuning machines (I faint at the memory) and over-spun

bronze guitar strings for basses. He had a good time with it.

The most memorable line was (in a thick German accent) "You could pull

Mac truck with these strings!" Well, he was right and I went back

to the drawing board. That day I saw a rebec being carved, a huge

bass fiddle in the making, cabinets of gleaming tools, his collection

of delicate snakewood viol bows, and what Kelicheck referred to as the

most valuable items in the workshop, his cabinet full of instrument forms,

which represented a lifetime of manufacture. From that day I realized

the importance of working from an historical model and gave up my artistic

interpretations. I do miss the fun of designing "fantasy instruments"

as you could call them, and maybe some day I will return to the idea.

UPDATE 09/15/06 - George has started exhibiting at the North Georgia Foothills

Dulcimer Assoc. shin dig at Unicoi. I got to tell him my Sean Ryan story

and get in an arguement about whether keys belonged on recorders.

Kevin

Dunn.

If you're a maker, it pays to be a good musician as well. If you

are not terribly good, as in my case, then the next best thing is to be

friends with a terribly good musician. I met Kevin the very first

evening I sat in with Martha Bishop's group at St. Bart's. This

would have been in 1995, during my first year out of school. He

must have identified me as a fellow kook and perhaps not quite as stuffy

as the other patchy-elbows that were in that group. At any rate,

Kevin has been a great test pilot for my instruments. I even put

together his EMS cittern kit. His performance days go back to the

late 60's and he had the greatest notoriety with his group The Fans, which

was on the cutting edge of the early 80's post punk scene. He was

running around with the members of R.E.M. before they escaped obscurity

and, if I remember correctly, even had a hand in producing the B-52's

very first single. His follow-up group, Kevin Dunn and the Regiment

of Women, put out a couple of smashing great albums and we're all waiting

for the inevitable revival. His main instrument is guitar, in every

conceivable genre, but like me is undaunted by anything with strings and

has had in his collection, saz, charango, mandolin,lute, cittern, and

a theorbo that looks an awful lot like a dreadnought with nylon strings.

Robert

Cunningham.

Robert is another Atlanta maker with national, perhaps international,

recognition. He makes Harps principally and was introduced to me

by my friend Pam Kohler-Camp, who has one of his instruments. Also of

the engineering mind (actually, I believe he was a chemistry professor

at Emory University before turning to harps), he has the distinction of

having a workshop cleaner than my grandmother's kitchen, which is a hard

thing to do. Bob had a music store in the Virginia Highlands neighborhood

in Atlanta for some years in the early 80's (before my days here), and

I gather brought a source for ethnic and early instruments at a time when

there were few to be had. Bob uses gut strings for some of his

instruments and was a great source for me when I was stringing up my first

vielles. He had the mathematic wherewithal to set my string gauges

for me. I have always thought that getting a peek at a maker‚s

workshop was worth a hundred questions about his work. Bob‚s

is one of my favorite to visit: a maze of basement rooms with well ordered

tool cabinets and wood storage, opening on to a long-cultivated Japanese

garden. And despite the work that goes on there constantly,

I have never found even a shaving of wood on the floor. Recently I have

turned to Bob as a resource for the koto, of which I am pursuing a commission.

He has a long history with Japanese instruments and I had the good

fortune to document a couple of his specimens. I admire the fact

that he has risen to the top of his field in Harps but has had the industry

over the years to produce so many other types of instruments. He

has made early keyboard instruments including spinets and a portative

organ, zithers, and many styles of harps besides the ones he has chosen

for production. He is also an inventor, an aspect of making to

which I personally aspire.

Ken

Bloom.

A very recent acquaintance, Ken I have met only once over a weekend at

the Dulcimer gathering at Unicoi, but mention him here for that great

lesson. He teaches historical performance up in North Carolina

and makes instruments for his use and other "living history" folk.

Also somewhat of an inventor, he had his newly-recorded "bowed dulcimer"

(not related in form to the historical instrument). He also had

a fine example of the Norwegian langeleik which I documented. I

asked Ken for his opinion on the scheitholt I had brought, and I had my

eyes opened to another instance of my cross pollinating instruments and

winding up with something that was not quite what I was calling it.

My "scheitholt" with its raised fingerboard, modern dulcimer-like three

string D-A-D tuning arrangement, and zither wrest pins was hardly the

simple, twanging instrument of 18 th c. origin. Of course, I had

consciously modified the instruments I had documented in the Smithsonian,

but the point was I had an instrument that, although vaguely resembling

those instruments, in essence was no longer the same creature.

He likend my creation more to the 19 th c Austrian volkszither, made famous

by mad king Ludwig's patronage. I hate it when I have to learn

a lesson twice. I will continue to make my "improved scheitholt."

- innovation must be a part of any self-respecting craftsman -

but perhaps I will choose the titles for my works a little more

carefully. ADDEMDUM 2005 -- I saw Ken again at Mountain Dulcimer Week

at Cullowee. Besides getting to spend more jam time with Ken, I got to

study with other dulcimer luminaries, some of whom I had met at Unicoi:

I got to study with Ralph Lee Smith on dulcimer history and inspect his

collection of early dulcimers and scheitholts which were on display at

the university museum, I had a ballad class with Betty Smith (no relation)

where we dissected Barbra Allen, a great lesson in minute vocal inflections.

I had vocal coaching and some great conversation with Flora MacDonald

and Don Pedi and I had the history of Galax with Phyllis Gaskins and her

husband was kind enough to give me an old-time fiddle lesson after class.

Paul

Hamler.

Paul has nothing to do with music other than to note that Willy Nelson

seems to always be playing when I'm at his workshop. Paul is quite

well known in his circle as a machinist and maker of historic handtools

in miniature. Here is the strangest story of six-degrees-of-separation

in my meeting him. It begins with Harry vas Dias, who asked me one day

if I had ever crossed paths with (now I forget his name), a semi-professional

violin and guitar maker living just around the corner in the Emory area.

I went to him to soak up all I could. I believe it was the

subject of my Treadle lathe I was making, or perhaps it was when he found

out I lived in Snellville, which edged him to mention did I know of Paul

Hamler? I had never heard of him. The more I described the

geography of my house in Snellville, it became apparent that we were talking

about someone who lived in my Very Subdivision, a mere walking distance

from my own house. I had to hang out in Atlanta for 10 years to

meet someone who was living on my doorstep in Snellville all that time!

I always pay close attention to those star-crossed moments in life.

Well I have known Paul only about a year now, but he has turned

into quite a generous friend in helping me with my various projects that

require metal or any mechanical operation. And it is always a privilege

to be able to associate with someone who is truly top in his field.

I am loosing track of the number of books and publications in which I

have seen his work. I like pointing to a coffee-table edition book

on antique tools in the Highland Hardware and saying, this guy lives down

the street from me. Cool.

Grant

Tomlinson and Andrew Rutherford .

Mentioned together because I met them both, after years of knowing their

work in name only, at the 1999 Lute society gathering at Case Western.

Considered by the lute community to be two of the finest makers,

on this continent at least [Grant in Vancouver, Andy in

NYC], I had a great opportunity to study with Andy for a week and to interview

them both about their work and personal history. It was here at

Case Western that my "good enough" philosophy was dispelled and I began

a new chapter as a craftsman. I refer to an idea that aquired,

by fair or foul, from Lundberg in his practicum. Although I'm sure

few would dispute Lundberg as one of the finest modern makers of the instrument,

he nonetheless had this "good enough" idea that did not, if I may interpret,

produce the model of excellence. He referred to the Masters of

the renaissance using local woods that were perhaps not the best tone

woods but were "good enough" to make a playable instrument. He

supposed that the bulk of instruments produced in those times were working

men's instruments and not the glistening examples we see preserved in

museums with their ivory bodies and gilded roses. The instruments

were not meant to last beyond a lifetime. They were made "good

enough". So in 1999 my attention to detail lacked much to be desired

and I drew a skeptical eye from my mentors apparent. Case Western was

an eye opener. I had never before seen so many lutes and like instruments

in one place, nor of such great quality, nor players of such great ability.

It was almost too much to take in at once and I felt very much

out of my element. I matured greatly that week, turning from a

sort of early music groupie, idolizing the figureheads, to being a student

who understood his place in the ladder of the profession. Depressingly,

that rung was a low one and unfortunately I fear the impression I left

with my teachers was of the former persona and not of the latter.

But these people were connections nonetheless and I hope to make future

use of them. I also mention Richard Fletcher, who was there

and by my impression a sort of father-figure to Grant and Andy.

I knew I was in the presence of greatness when I realized it was he who

had done the restoration of the Venere soundboard fragment in the Met

collection which I had marveled over just a few years before. Consorting

with and questioning the man behind a restoration that I myself had traveled

to study: quite the feeling of being "inside".

Daniel J. Betsill

2004

Bring it HOME.

Instruments in progress: Cittern, Baroque Guitar, Mountain Dulcimer, Experimental

Dulcimer with bowed back

Is it not strange that sheep's guts should hale souls out of men's bodies?

-Shakespere, Much Ado About Nothing

"Now,

I have repeatedly remarked that all spiders, when the shrill humming of

an insect caught in a web is heard near them, become agitated, like the

Pholcus, and will, in the same way, quit their own webs and hurry to the

point the sound proceeds from. This fact convinced me many years ago that

spiders are attracted by the sound of musical instruments, such as violins,

concertinas, guitars, &c., simply because

the sound produces the same effect on them as the shrill buzzing of a

captive fly. I have frequently seen spiders come down walls or from ceilings,

attracted by the sound of a guitar, softly played; and by

gently touching metal strings, stretched on a piece of wood, I have succeeded

in attracting spiders on to the strings, within two or three inches of

my fingers."

-William Henry Hudson from The Naturalist in La Plata

The North American musicologist Alan Lomax argued in his book Folk Song Style and Culture that the structure of [a culture's indigenous] music. . . - essentially leaderless ensemble - emanates from and mirrors egalitarian societies. . . I love his theory that music and dance styles are metaphors for the social and sexual mores of the society they emerge from. Some say that the instruments [for this music] were all derived from easily available local materials, and therefore it was convenience (with a sly implication of unsophistiction) that determined the nature of the music. This assessment implies that these instruments and this music were the best this culture could do given the circumstances. But I would argue that the instruments were carefully fashioned, selected, tailored and played to best suite the physical, acoustic, and social situation. The music perfectly fits the place where it is heard, sonically and structurally. It is absolutely ideally suited for this situation - the music, a living thing, evolved to fit the available niche."

-David Byrne from 'How Music Works'